The one common denominator in the microcomputer era was ASCII. These 128 codes (zero through 127) provided a modicum of consistency for text files shared between the abundant computer platforms from days of yore. But a byte (char) holds 256 values. So what was done about those non-ASCII character codes, 128 through 255?

Never mind that in the early 1980s storage media was incompatible between platforms! You couldn’t take a diskette from an IBM PC and use it on an Apple II or TRS-80. Should you get the file to another computer, those 128 ASCII characters were read as-is. The rest of the codes, however, were assigned different characters, or character attributes (such as inverse text), on each system.

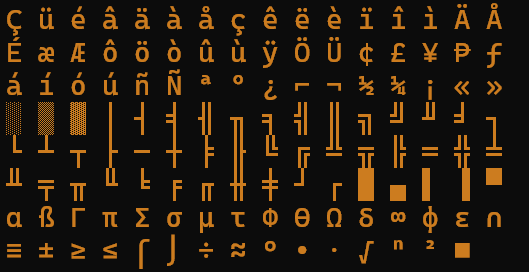

On the IBM PC, character codes from 128 through 255 were originally called “extended” ASCII. These characters were non-standard, but widely used thanks to the popularity of the IBM PC and its various PC clones. The extended ASCII character set is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The original IBM PC “extended” ASCII characters, also known as Code Page 437.

Eventually, it was recognized that the 128 extended ASCII characters weren’t enough. To add more characters, the code page concept was developed. This technology provided a set of 128 characters assigned to code values 128 through 255. The original extended ASCII character set became known as code page 437.

When the Unicode standard was developed, the contents of code page 437 were mapped to various Unicode values. The mapping isn’t consecutive, unlike other Unicode character sets, but the original code page 437 characters are there. In fact, I coded a program to output these characters, which is used in Figure 1. The array of code page 437 Unicode values also appears in the following code, which outputs these values with their hexadecimal and decimal value equivalents.

2025_12_20-Lesson.c

#include <locale.h>

#include <wchar.h>

#define GREEN "\e[32m"

#define NORMAL "\e[m"

int main()

{

wchar_t extended_ASCII[] = {

0x00C7, 0x00FC, 0x00E9, 0x00E2, 0x00E4, 0x00E0,

0x00E5, 0x00E7, 0x00EA, 0x00EB, 0x00E8, 0x00EF,

0x00EE, 0x00EC, 0x00C4, 0x00C5, 0x00C9, 0x00E6,

0x00C6, 0x00F4, 0x00F6, 0x00F2, 0x00FB, 0x00F9,

0x00FF, 0x00D6, 0x00DC, 0x00A2, 0x00A3, 0x00A5,

0x20A7, 0x0192, 0x00E1, 0x00ED, 0x00F3, 0x00FA,

0x00F1, 0x00D1, 0x00AA, 0x00BA, 0x00BF, 0x2310,

0x00AC, 0x00BD, 0x00BC, 0x00A1, 0x00AB, 0x00BB,

0x2591, 0x2592, 0x2593, 0x2502, 0x2524, 0x2561,

0x2562, 0x2556, 0x2555, 0x2563, 0x2551, 0x2557,

0x255D, 0x255C, 0x255B, 0x2510, 0x2514, 0x2534,

0x252C, 0x251C, 0x2500, 0x253C, 0x255E, 0x255F,

0x255A, 0x2554, 0x2569, 0x2566, 0x2560, 0x2550,

0x256C, 0x2567, 0x2568, 0x2564, 0x2565, 0x2559,

0x2558, 0x2552, 0x2553, 0x256B, 0x256A, 0x2518,

0x250C, 0x2588, 0x2584, 0x258C, 0x2590, 0x2580,

0x03B1, 0x00DF, 0x0393, 0x03C0, 0x03A3, 0x03C3,

0x00B5, 0x03C4, 0x03A6, 0x0398, 0x03A9, 0x03B4,

0x221E, 0x03C6, 0x03B5, 0x2229, 0x2261, 0x00B1,

0x2265, 0x2264, 0x2320, 0x2321, 0x00F7, 0x2248,

0x00B0, 0x2219, 0x00B7, 0x221A, 0x207F, 0x00B2,

0x25A0, 0x00A0

};

int x;

/* set the locale for wide characters */

setlocale(LC_ALL,"");

for( x=0; x<=127; x++ )

wprintf(L"%02X %03d %s%lc%s\n",

x+128,

x+128,

GREEN,

extended_ASCII[x],

NORMAL

);

return 0;

}

The extended_ASCII[] array is composed of wchar_t data types, wide characters. The values correspond to code page 437 character codes 128 through 255. You see that the array’s values aren’t sequential, but they accurately represent the original characters.

A for loop outputs all 128 values. The wprintf() statement uses the L prefix to make its formatting string wide; the %lc placeholder represents a wchar_t value. The GREEN and NORMAL defined constants represent ANSI color codes, so that the extended ASCII characters are output in green text. Here’s a truncated sample run:

80 128 Ç

81 129 ü

82 130 é

83 131 â

84 132 ä

85 133 à

86 134 å

87 135 ç

...

F8 248 °

F9 249 ∙

FA 250 ·

FB 251 √

FC 252 ⁿ

FD 253 ²

FE 254 ■

FF 255

You might be curious about character 255. It’s a “blank.” This character isn’t a space; it’s Unicode U-00A0. It’s different from the space character (U-0020) but it appears the same.

For next week’s Lesson, I combine these characters with the wide characters for the ASCII control codes to finally update my own colorful version of the hexdump utility.

Could be a starting point for future articles on character encodings,

→ single-byte character encodings like (extended) ASCII

→ multi-byte encodings (like Shift JIS [Windows, MacOS] or EUC-JP [Uɴɪx, Linux] for Japanese)

as well as how libiconv/iconv allowed one to work with such text… and how the development of Uɴɪᴄᴏᴅᴇ finally made it possible to unify all these disconnected islands of various characters.

(Even if it turned out that the initially favored UCS-2/UTF-16 encoding was a mistake, a multi-byte encoding such UTF-8 being better suited to the task.)

Just an idea ☺

Thank you!

Did you find the IBM Extended ASCII to Unicode mappings somewhere or did you have to assemble them yourself? If so it must have been tedious and boring. Is there one for ISO 8859 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO/IEC_8859-1 or Windows 1252?

Python comes with a built in data structure with details of the whole of Unicode including descriptions and categories, eg.

265D

BLACK CHESS BISHOP

Symbol, other

I don’t know whether there is something similar for C, possibly lurking in some obscure corner of Github.

I asked ChatGPT to build the array for me.